Key takeaways

- Women and minorities faced credit discrimination for decades.

- The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 made it easier for both groups to obtain credit cards and loans.

- The act includes rights and protections for consumers applying for credit.

I am a single Black woman, and I can apply for a credit card all by myself.

Thankfully, this is an easy (and obvious) declaration for me to make today. Unfortunately, it wasn’t so long ago that things were a lot more complicated. Before 1974, it was perfectly legal for lenders to deny me credit based solely on my gender and race.

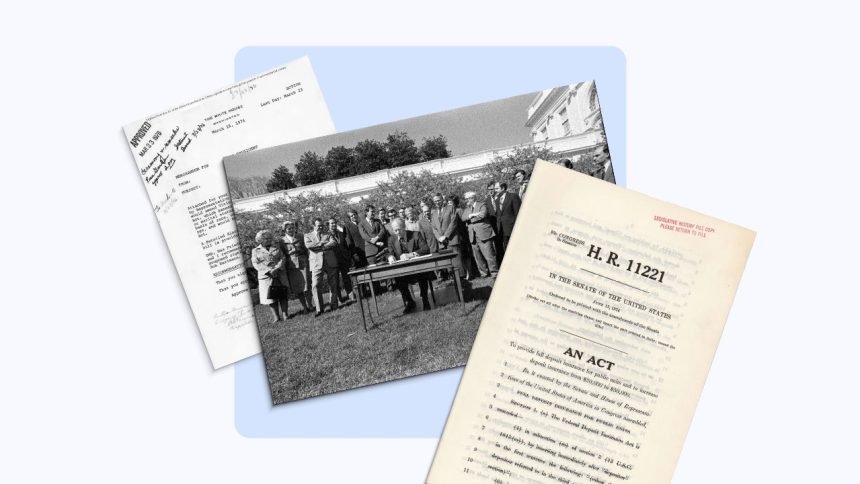

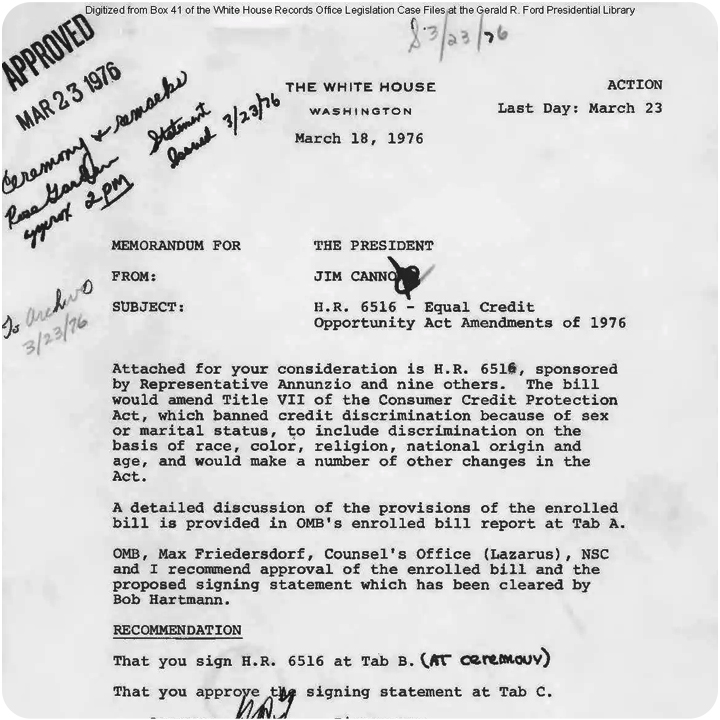

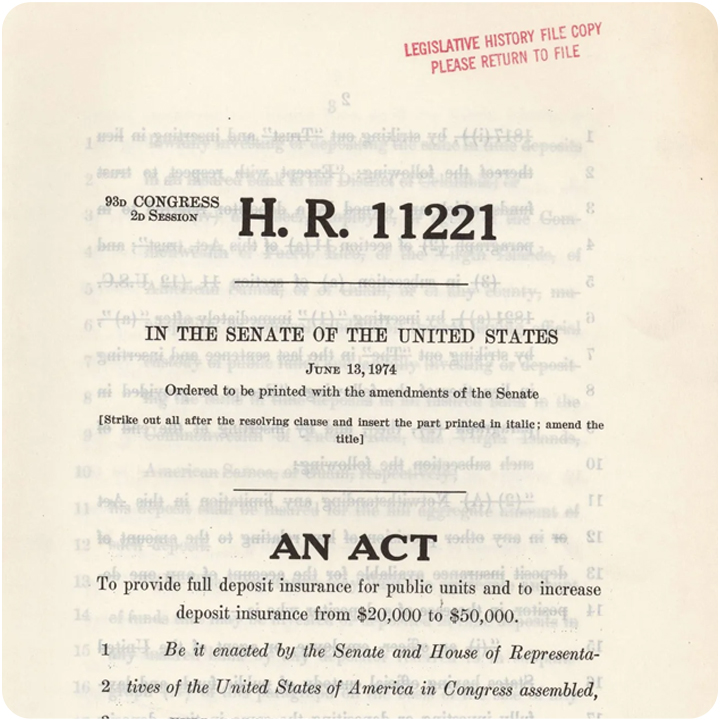

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 (ECOA), signed by President Gerald Ford 50 years ago on Oct. 28, 1974, changed that. It prevented creditors from discriminating against an applicant because of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age or participation in public assistance programs. In 2021, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) Regulation B added protection for sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination. That has leveled the playing field for everyone with full access to the U.S. credit industry.

I’ve written about credit cards since 2018, and my mission has always been to help people get smarter about credit cards and how they fit into a person’s money strategy. So to celebrate the 50th anniversary of this important legislation, let’s give thanks for this list of things many of us take for granted today that are possible thanks to this legislation.

Loans and credit

As a woman, I would have been routinely denied credit cards, mortgages and loans before 1974. The only way around this was asking my husband, father, uncle or a male friend to be a co-signer. As a woman, I would have been routinely asked personal questions that had no bearing on my creditworthiness, including about my lifestyle, my marital status and plans to have children.

It was even worse for minorities. I would have faced automatic refusal when applying for cards or loans with flimsy excuses by banks such as citing insufficient collateral (despite my having it). I could forget asking male friends or relatives to co-sign for me – that would’ve been a non-starter considering they were also minorities.

In 1970, only 16 percent of U.S. households had at least one credit card; the rate is now 77 percent as of 2024, according to The Ripple Effects of the Great Credit Expansion,” a report from the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth University. ECOA caused a “cascade of improvements to credit access,” including deregulated lending markets, more interstate competition, softened bankruptcy laws and the emergence of the credit score. Taken together, this led to a democratization of credit.

Consumers now have access to nearly 4,000 issuers, along with dozens of co-brand merchant partners and four major networks, as noted in the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s 2023 “The Consumer Credit Card Market” report. This has spawned myriad consumer options, including credit card points, miles and perks, debt consolidation products, customized financial planning and tools to dig yourself out of debt.

Home ownership

Before 1974, it was extremely difficult to buy a home if you weren’t a white man. My grandfather, an officer in the U.S. Air Force for 30 years, was only able to buy his home in 1970 for two reasons. First, the Fair Housing Act (Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968) expanded on previous acts and prohibited discrimination based on race, religion, national origin, sex, (and as amended) handicap, family status, gender identity and sexual orientation.

Second, although my grandfather had access to the GI Bill, which offered home loans requiring no money down, fewer mortgages were granted to Black Americans due to routine discrimination. Fortunately, he worked for Bank of America as a loan officer and eventually a branch manager, which allowed him to get a mortgage — at a better interest rate — as an employee.

Working women were required to find a male co-signer even if they had a down payment and the means to pay their mortgages. We’ve come a long way, but there’s still room for more progress.

Single women own 20.3 million homes in the U.S., compared to single men, who own 14.9 million homes; married couples own 49.3 million homes in 2024, according to the Census Bureau.

In 2023, Asian homeownership for single females was 360,902, single males were 268,540 and married couples reached 3.1 million, according to numbers from the National Association of Realtors (NAR). Single Black females reached 1.2 million, single males were 770,725 and married couples were at 2.9 million. Single Hispanic females were at 710,631, single males were 685,294 and married couples reached 5.8 million.

NAR found that nearly eight and half million White single women owned homes in 2023, while single white males owned 6.5 million homes. White married couples owned 37.6 million homes. Despite the progress, the numbers clearly show biases against these minority groups continue to persist in present times.

Credit scores

In the olden days, lenders could literally create their own criteria when it came to who could – and couldn’t – get access to credit.

In 1989, the Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO) invented the first consumer credit score. In 2006, Equifax, Experian and TransUnion joined together to create VantageScore as an alternative to FICO.

The act paved the way for credit-scoring models that gave lenders a fast, easy and, most importantly, an equitable way to determine an applicant’s risk level for a loan.

Credit scores help keep lending practices fair for all by ensuring decisions are based on factors such as payment history and length of credit history and not on factors such as age and marital status.

Student loans

The first federal student loans, along with grants and scholarships, provided under the National Defense Education Act of 1958, were funded by the U.S. Treasury. However, they were primarily just for students majoring in engineering, math, education, science and foreign languages.

President Lyndon B. Johnson paved the way to make student loans more equitable to all when he signed the Higher Education Act of 1965, which made postsecondary education more accessible to low- and middle-income families, according to the liberal think tank New America. Part B of the act included provisions related to anti-discrimination based on race, religion, sex, or national origin that mirrored the Equal Credit Opportunity Act.

Consumer protections

Before the passage of ECOA, lenders didn’t have to reveal interest rates and could selectively force some customers into higher-interest loans. It was almost impossible to fight credit report errors and privacy protections were non-existent.

ECOA changed that by offering credit protections and rights for consumers. If a lender rejects an application, it’s required under ECOA to give specific reasons an application was rejected or tell you that you have the right to learn the reasons if you ask within 60 days.

If your application is based on your credit report, the lender is required to do the following: Provide the numerical credit score used in the rejection and key factors that affected your score; receive contact information of the credit reporting company providing the report; inform you of your right to get a free copy of your credit report provided it’s within 60 days of the rejection; and explain what it takes to fix mistakes or add information for a more complete report.

The Federal Trade Commission also entitles you to the following:

- The ability to keep your own accounts after events including name and marital status changes.

- Know whether your application was accepted or rejected within 30 days of filing an application.

- Know why a creditor rejected your application by telling the specific reason for the rejection or tell you that you are entitled to learn the reason if you ask within 60 days.

- Learn the specific reason a creditor offered you less-favorable terms than you applied for, but only if you reject these terms.

- Find out why your account was closed or why the terms of the account were made less favorable, unless the account was inactive or you didn’t make payments as agreed.

Protect your rights

If you wanted to apply for a loan or a credit card before 1974, you faced obstacles including gender and race discrimination and redlining. Lenders routinely denied applications and charged higher interest rates or fees for car loans, credit cards, home loans, student loans and small business loans to consumers who had little recourse.

But now if you believe a lender has discriminated against you, first reach out and ask if your application can be reconsidered. If that doesn’t work, report a potential violation to the correct federal agency based on information given to you by the lender that rejected your application, says the CFPB.

If you believe a lender discriminated against you, there are options. You can submit a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), with the CFPB online or by calling 1-855-411-CFPB (2372). You can also file a complaint with your state attorney general or state consumer protection offices. Those in the military can report discrimination to their installation Judge Advocate General (JAG).

You can sue a creditor in federal district court. If you win, you can recover actual damages, punitive damages under certain circumstances and lawyers’ fees and court costs.

The bottom line

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act, currently enforced by six different federal agencies, isn’t perfect. But it does provide a framework to ensure more fairness in consumer lending.

The Justice Department regularly sues lenders that discriminate against minority consumers, as outlined in the CFPB’s Fairway Mortgage settlement. The Federal Trade Commission has battled car dealerships for discriminating against Black and Hispanic customers by charging them higher prices for vehicles and unwanted add-ons such as special coating paint and “upgraded” floor mats.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has issued guidance to national banks and federal savings associations on “buy now, pay later” lending to ensure that lenders offer fair access to financial services, support fair treatment of consumers, and comply with applicable laws and regulations.

When you consider what lenders could do before ECOA was enacted, there’s no doubt that millions of Americans have benefitted from a credit industry that has provided more equal opportunities and fairness, with less discrimination and exclusion.

Read the full article here